The Weir at Bath with Pulteney Bridge

I have stood with my father on Grand Parade, looking across at the weir thousands of times, sometimes with a sticky bun from Sally Lunn’s, a pastie from the arcade or best of all a pig’s cheek from the guildhall market, and my father must have attempted to capture the scene hundreds of times too, and yet I had no definitive painting of it.

The bridge itself was designed by Robert Adam inspired by his trip to Florence and Venice and is one of only four bridges in the world with shops along both sides like this. In his drawings of it, my father is confident in its straight lines and wide curved arches.

But it is the river, not the bridge that is the subject of the painting, and in this version, we see it exploding with energy and sheer joy over the steps of the weir. Dark, cold and static on the left-hand side it boils with excitement on the right, trying to capture the sun as it swirls off into the future.

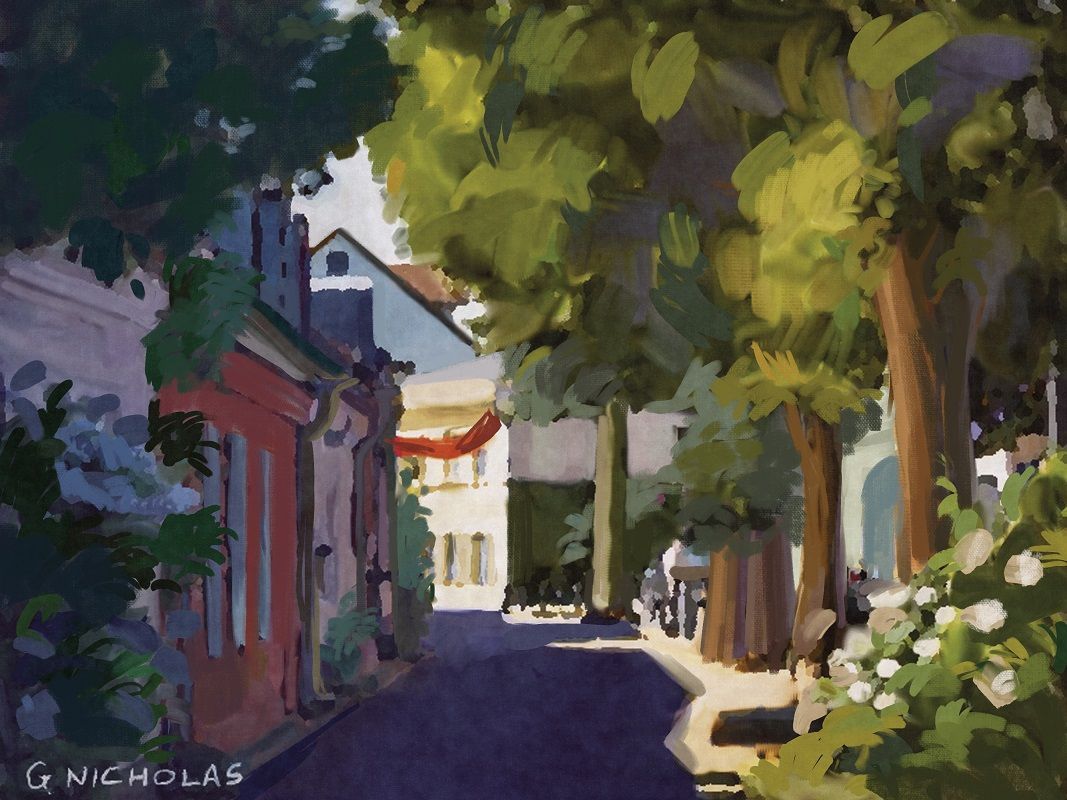

This picture has him scurrying over the bridge, which appears in a blur, to the clearly defined restaurant at the centre, before a post-lunch haze of trees blurring in the sun.